The Unnatural Legal Geographies of the Current US ‘Megadrought’

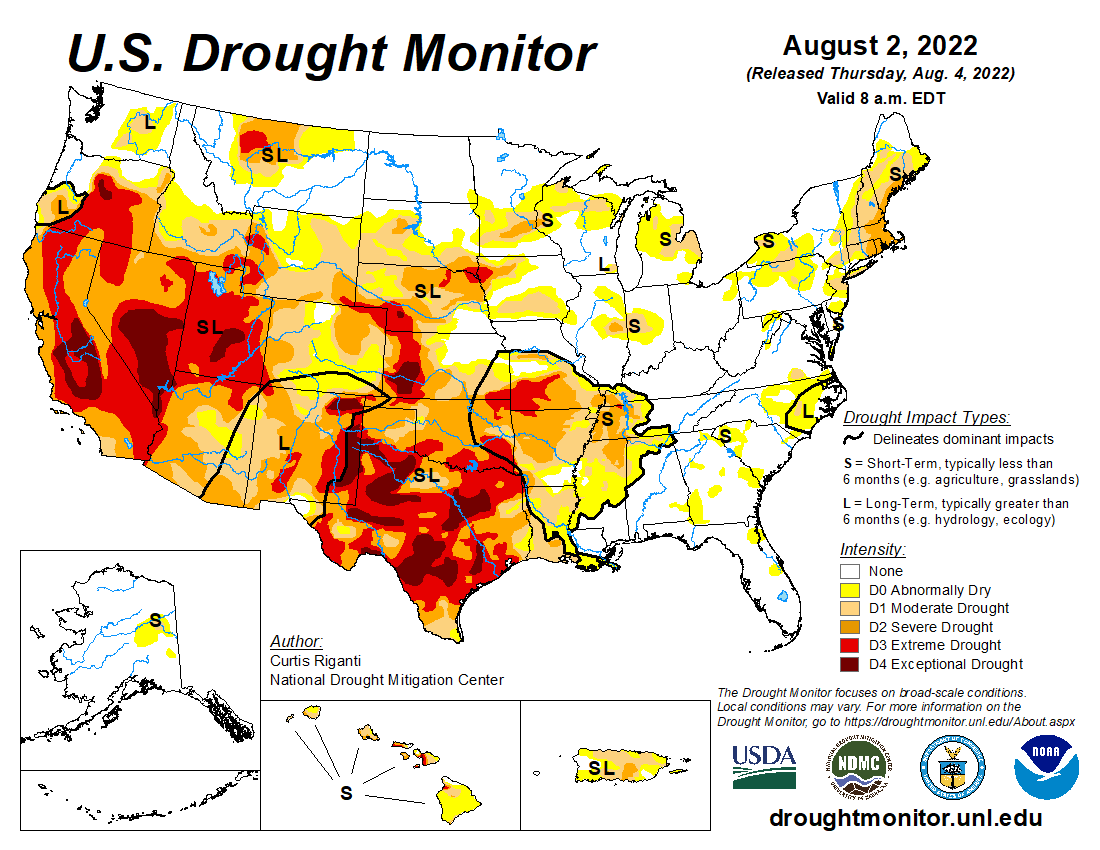

Extreme drought is ravaging much of the Western United States as water reservoirs and snowpack decline to dangerous levels. As panicked water managers seek immediate solutions to the impending crisis, the current “megadrought” also raises an important but often ignored question: what role does law play in creating and exacerbating unequal access to shrinking water resources?

U.S. drought conditions, summer 2022. Source: U.S. Drought Monitor

Legal political ecology, which integrates questions of law, political economy, and environmental issues, provides an important and useful toolkit for answering this question and developing a critical understanding of contemporary social-ecological problems like drought.

Although shrinking water resources may seem like a natural phenomenon, a drought is not just a meteorological condition. While it is clearly tied to precipitation patterns, drought is not just about a lack of rain.

Drought can be better understood as the relationship between how much water is available and how much water is expected to support the needs of human and nonhuman water users. And, when water dries up, it doesn’t dry up the same for everyone (or every animal). Instead, water availability during drought is experienced differently depending on access, which is in turn related to questions of both law and political economy.

Experiences of drought are inherently related to legal questions. How is water allocated, where, and to whom? Who is allowed to access and use what quantities of what water in what place? If there is less water than expected, who gets it and who loses out?

In practice, these questions are answered by water law. For example, in the Western United States, the “prior appropriation doctrine,” developed over a century ago, allocates water using a ‘first in time, first in right’ system that gives more secure rights to earlier (i.e. more senior) water users.

What this means is that some people are given greater access to water, while others have less access. As a result, drought, as a phenomenon that is mediated by law, is experienced differently by various communities of humans and nonhumans, as the following examples illustrate.

Prior appropriation water law has been critiqued as a tool of colonialism and dispossession. This legal principle disproportionately benefits irrigated agriculture, which accounts for 70 to 80 percent of all water extraction. As a result, other water users- particularly Indigenous peoples who depend on healthy river systems for fish, an important First Food- lose out. The experience and impact of drought is unequal, racialized, and fundamentally shaped by law.

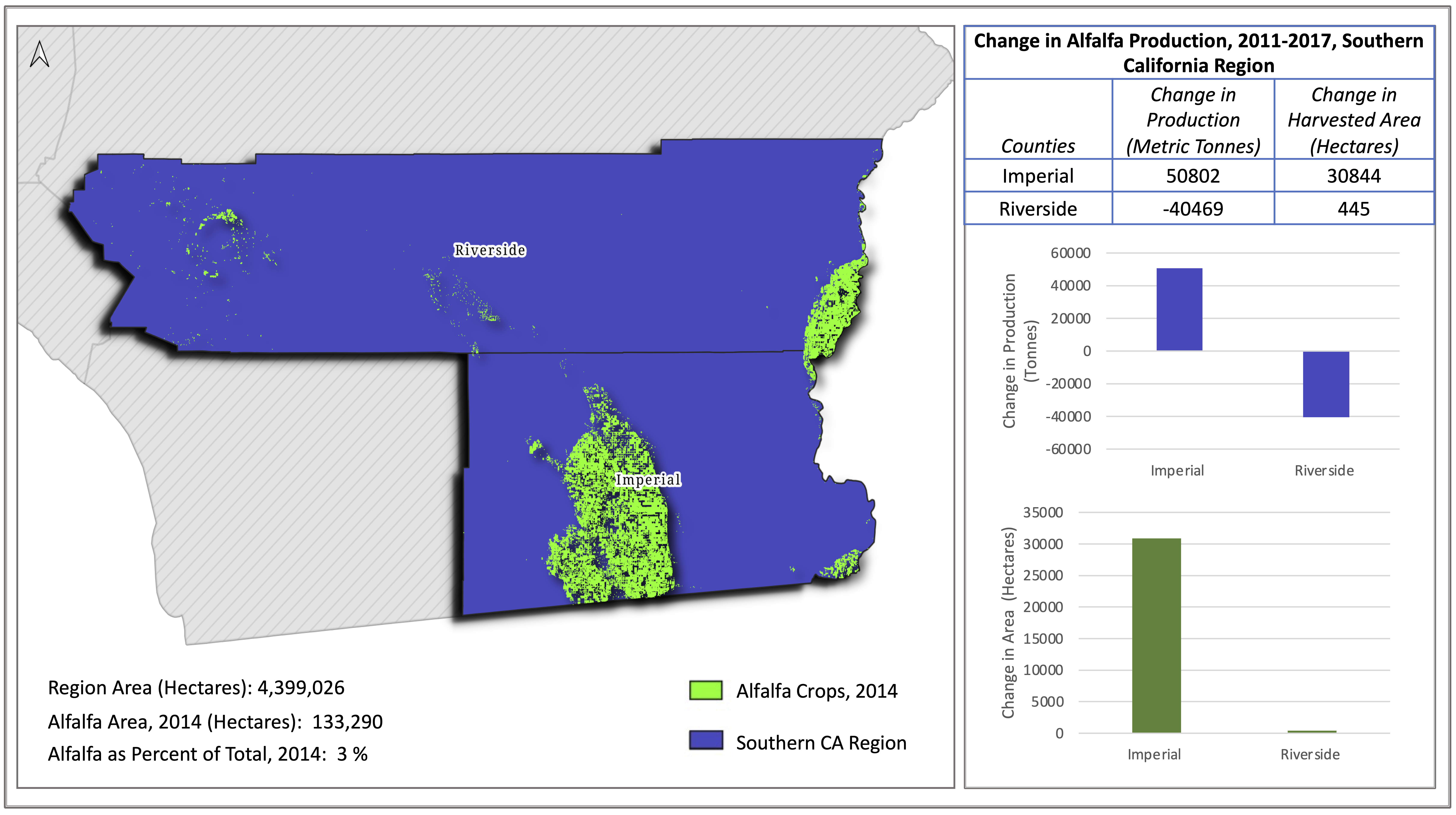

Some people with resources and privilege are able to maintain water access even during times when precipitation is scarce. For example, in recent research, I examined the production of alfalfa, a particularly water-intensive crop, in California during the 2014-2017 drought.

One might expect that during times of severe drought, alfalfa farmers would move away from producing such a high-water-use crop. Our research found the opposite to be true. In fact, during a time of severe drought, we found that alfalfa production actually increased in some areas of California with particularly secure water access via prior appropriation.

This finding highlighted that, when it came to farmers’ experiences of drought, legal access to water through antiquated systems of prior appropriation water rights mattered more than actual precipitation patterns.

Map shows Southern California’s alfalfa production lands in 2014; graphs (right) show changes to alfalfa production from 2011–2017. Source: Cantor et al, 2022.

There are others who are quick to experience water insecurity when water resources dwindle. Disparities in water access are also directly tied to money and resources, bringing questions of political economy to the foreground.

For example, two news articles published during the California drought (mentioned above) highlight these disparities. One article describes the lush green lawns of the large estates of celebrities, who have no problem paying whatever it takes for water, while the other describes household taps running completely dry in low-income Californian communities.

Despite laws that declare every person in California has a right to clean, safe, and affordable drinking water, many decades of ineffective and inadequate groundwater regulation have led to today's situation of declining groundwater levels, which in turn causes domestic wells to run dry. Drought is clearly experienced differently depending on how much one is able to pay, where one is located, and whose water uses are prioritized under law.

Through a legal political ecology lens, we can understand drought as differentially experienced, mediated through legal structures (such as water rights) and political economic structures (such as class). Legal political ecology emphasizes the interactions between legal and political economic systems that together, in this case, shape who has unfettered access to water and whose taps run dry.

The following bibliography will help you learn more about legal political ecology.

Legal political ecologies of water

- Borgias, S. L. (2018). “Subsidizing the State”: The political ecology and legal geography of social movements in Chilean water governance. Geoforum, 95, 87-101.

- Cantor, A. (2016). The public trust doctrine and critical legal geographies of water in California. Geoforum, 72, 49-57.

- Cantor, A., Kay, K., & Knudson, C. (2020). Legal geographies and political ecologies of water allocation in Maui, Hawai 'i. Geoforum, 110, 168-179.

- Cantor, A., Turley, B., Ross, C. C., & Glass, M. (2022). Changes to California Alfalfa Production and Perceptions during the 2011–2017 Drought. The Professional Geographer, 1-14.

- Gillespie, J., & Perry, N. (2019). Feminist political ecology and legal geography: A case study of the Tonle Sap protected wetlands of Cambodia. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 51(5), 1089-1105.

- Kelly, S. H. (2021). Mapping hydropower conflicts: A legal geography of dispossession in Mapuche-Williche Territory, Chile. Geoforum, 127, 269-282.

- Whear, J. (2022). The legal geography of prior appropriation water rights: Political ecology and the defeat of the Las Vegas Pipeline. Geoforum, 132, 62-71.

Legal political ecology, more broadly

- Andrews, E., & McCarthy, J. (2014). Scale, shale, and the state: political ecologies and legal geographies of shale gas development in Pennsylvania. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 4(1), 7-16.

- Delaney, D. (2017). Legal geography III: New worlds, new convergences. Progress in Human Geography, 41(5), 667-675.

- Kay, K. (2016). Breaking the bundle of rights: Conservation easements and the legal geographies of individuating nature. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(3), 504-522.

Colonialism and water law

- Berry, K. A., & Jackson, S. (2018). The making of white water citizens in Australia and the western United States: Racialization as a transnational project of irrigation governance. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(5), 1354-1369.

- Curley, A. (2019). “Our winters' rights”: Challenging colonial water laws. Global Environmental Politics, 19(3), 57-76.

- Norgaard, K. M. (2019). Salmon and acorns feed our people: Colonialism, nature, and social action. Rutgers University Press.

- Wilson, N. J., Montoya, T., Arseneault, R., & Curley, A. (2021). Governing water insecurity: navigating indigenous water rights and regulatory politics in settler colonial states. Water International, 46(6), 783-801.