Subterranean Legal Geographies: Regulating Groundwater in California

It will come as no surprise that cities in Southern California depend on water that originates far away. But a new change to the Colorado River compact, an agreement that divides the Colorado River’s water among the states that border it, threatens a quarter of Southern California’s water supply, driving residents’ source of water—as well as legal battles over access to this water—underground.

Even in good times, groundwater, or water underneath the land’s surface, supplies approximately one third of California’s water supply. As a result of coming changes to the Colorado River compact, California will be searching for new water sources. In times of need, Californians have often turned to groundwater to quench their thirst. Will a once-dead private groundwater project proposed in the Mojave desert become the solution?

As legal geographers have argued, water is a slippery thing to govern and regulate. Whether on the high seas of international waters or along rivers and creeks, water confounds easy commodification and regulation. This is profoundly true for aquifers that contain groundwater, which are hidden underground and often illegible to those above, leading scholars and water managers alike to refer to them as an “invisible resource”.

The search for new sources of water has (re)materialized in the Cadiz Project, a once-dead, controversial groundwater project that proposes to take groundwater from an aquifer deep in the Mojave desert and pipe it more than 200 miles to California’s coast. The project is often told as a Chinatown-style tale of a countryside drained by a city, in this case Los Angeles. Opponents charge that fossil water, likely deposited during the last ice age, should not be taken out now, while proponents see groundwater as a sound investment for California’s future.

Who determines how and when water can be taken out?

While some might expect scientists to determine how to divide the waters, it is actually a regulatory process that often plays out far from the public eye.

Historically, these decisions about how much water should be taken out only happens after an overpumping crisis. In other words, the decision is made only after one landowner sues another, after the groundwater table has dropped too much. The court then adjudicates the groundwater between overlying owners, which involves assigning each landowner a right to pump a certain amount of water based on the percentage of land that they own on top of the aquifer.

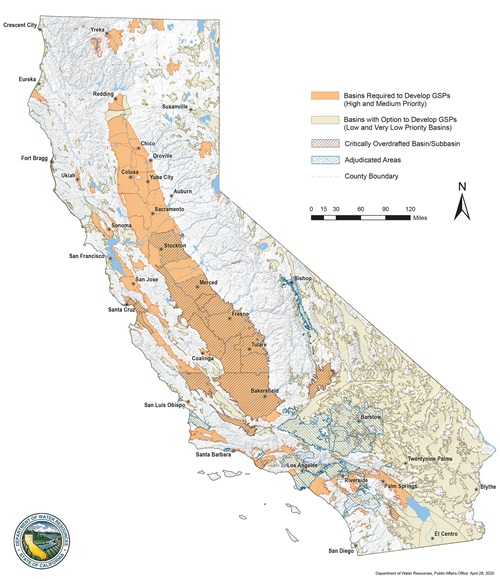

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this crisis-to-adjudication pipeline is not the best way to manage groundwater. In 2014, a new solution was introduced in the form of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), which forces groundwater users in already overdrafted areas to bring their use to a sustainable level—what is often called “safe yield”—by 2040 . In some areas like the agricultural Central Valley, however, any solution might already be too late.

Not everyone is subject to SGMA, though. Because the aquifer under the dry lakebed Cadiz owns has not been overpumped yet, the Cadiz area does not have to follow the new rules. The rules for Cadiz are like the rules in the old system—wait until someone sues. And since the federal government is the other major landowner in this area, it’s likely that Cadiz will be able to pump as much as they want until something goes catastrophically wrong.

But before they start, they need to pass a regulatory hurdle: the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, which regulates any development project on private lands, including water pumping schemes. The Santa Margarita Water District, who would be one of the major recipients of Cadiz’s water, sponsored the application.

Cadiz hired scientists and environmental compliance companies to write their environmental impact report, which serves as the document to justify how much water they plan to take out and sell.

Through examining their documents, I found that the “safe yield” for the project depends on how much water they think will be entering into the aquifer each year, which is called groundwater recharge. Groundwater recharges over time as surface water percolates into the aquifer.

Recharge is a normally considered a slow process. During this year’s atmospheric rivers in California, there were questions about whether the rains were sufficient to recharge aquifers and how California could best capture that water. And in ordinary years, any groundwater recharge is normally far exceeded by the water taken out of the aquifer—especially in chronically overdrafted areas like the Central Valley.

For the Cadiz project, though, the company estimates much higher recharge rates based on both the water that they think enters the aquifer each year as well as the water they think they are saving by preventing water from evaporating. The company estimates that 34,000 acre-feet/year recharge in their most recent documentation, whereas other investigators have estimated around one tenth of that number. This number—and the subsequent proposed pumping rates—are in regulatory documents that are not necessarily subject to the kinds of scientific scrutiny that there would be for a peer-reviewed paper. So Cadiz is able to pump more by claiming that the aquifer recharges more quickly than anyone else claims.

However, under the California Environmental Quality Act, there are no requirements for external scientific review. Instead, environmental reporting is run within the corporate structure, and normally approved by the reviewing agency that also has a financial interest in the project. This creates a newer version of the forms of “regulatory capture” that scholars critiqued in the construction of dams and large-scale water infrastructure during the 1950s.

While there is significant uncertainty in the subterranean spaces of the aquifer, Cadiz Inc has been able to monetize this uncertainty through making claims about the recharge rates. These claims, of course, cannot be fully proven or disproven until impacts of pumping out too much groundwater are too late. The desert, in other words, could become subject to the overpumping crisis that already took place elsewhere in the state.

In my article, I call Cadiz’s EIS an example of regulatory alchemy, a mode of making the water cycle and its temporality into a form of capital through regulatory documents. In other words, by betting on high—and potentially unrealistic—recharge rates, Cadiz Inc can promise future water to sell.

The problem with regulatory alchemy, of course, is that it is both over- and under-regulated. While the Environmental Review documents are thousands of pages long, they don’t address a fundamental problem: how did Cadiz get such high estimates from aquifer recharge in comparison to every other investigator, and what standards should we use to evaluate the science used in reports?

As we look to a future with less Colorado river in California and the booms and busts of climate change, large-scale water projects like Cadiz will likely only become more popular. As scholars, we’ll have to pay attention not only to the optics of the projects, but their regulatory documents, and how to reconsider EIS processes so that impacts are accounted for properly.

See Julia’s full article online here: Sizek, Julia. (2023) “Regulatory Alchemy: How the Water Cycle Becomes Capital in the California Desert.” Antipode. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12942.

For more information on water law and governance:

-

Blomquist, W. (1992.) Dividing the Waters: Governing Groundwater in Southern California. ICS Press.

-

Hundley, N. (2001.) The Great Thirst: Californians and Water—a History. University of California Press.

-

Bakker, K. (2000.) “Privatizing Water, Producing Scarcity: The Yorkshire Drought of 1995.” Economic Geography 76(1):4–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2000.tb00131.x.